I want to explain my solution to the readership problem I described in my last post. The solution is a little bit complicated and at different times I have described it in different ways, trying to come up with fancy acronyms like PIPPIN. However, we can just think of it as a magic formula for writing an effective case for support.

The way the magic formula works is that it creates the case for support as a series of layers. Each layer takes care of some of the needs of the very different groups of readers that matter. The readers that matter are those who participate in the funding decision. Remember, the case for support is the document that either convinces a grants committee to award you a grant, or doesn’t.

Who are the Readers that Matter?

There are three groups of readers who participate in the funding decision, ordinary committee members, presenting members and referees.

Ordinary Committee Members

Most of the votes that determine whether your application is funded come from ordinary committee members who have really deep expertise in areas completely outside the topic of your project. Unfortunately, when it comes to your topic, they probably don’t understand it. They may not even see why anyone would want to research it. You need to convince the ordinary committee members that your project is worth some of the money that might otherwise go to projects on topics that they know are important.

You don’t have much opportunity to convince them because your application is one of a very large bundle that they don’t really have to read. They only need to know enough about it to get through a discussion, in which they can remain silent, and vote on a score, for which there will be a recommendation. They will be much more concerned to spend time reading the applications that they have to present to the committee.

However, you do have a chance. They will want to decide whether to push your score up or down, which they can only do by understanding your application. However, bitter experience tells them that, for most grant applications, understanding does not come easily, if at all. They will want to check if yours is worth the effort. They will probably have a quick look at the introduction before the meeting. You have maybe 30 seconds to catch their interest.

If you do manage to catch their interest by persuading them that the topic of your research project might be important enough for them to want to see it funded, and that your application might be intelligible, they will dig a little bit deeper. They might spend five minutes skimming through your application trying to work out whether your project will make enough progress that it should be funded. They won’t understand your technical terminology. You have write in such a way that they can work out what they need to know from the context.

Presenting Members

A couple of committee members will know a bit more about your topic, and spend a bit longer reading your application. They may even think your topic is important, but they probably won’t be real experts. They will have the job of presenting your application to the rest of the committee, and recommending a score. They won’t have a huge amount of time to read the application because they probably have eight or nine others to present on the same day. You will probably have about an hour to make them expert enough to explain why the problem you are trying to solve is important and to master the detailed evidence that your project is likely to make good progress towards a solution.

Even if the presenting members are enthusiastic about your project, the score they recommend is likely to be quite conservative. A conservative recommendation is inevitable if the presenting members can’t understand the application; they will just follow the referees’ recommendations without much enthusiasm. However, even if they do understand an application, presenting members will be aware that they are not expert enough to know whether your work really leads your field, which means they have to be conservative in their recommendation. Their colleagues on the committee will be aware of their limitations, and so will be sceptical of over-enthusiastic recommendations. In a world of conservative recommendations, the enthusiasm of committee members can make the difference between success and failure.

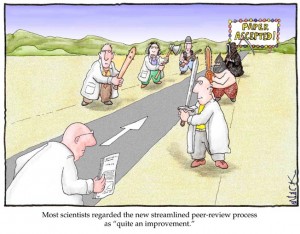

Expert Referees

Referees are real experts on your topic. They want to see detailed evidence that your topic is important and that the research questions your project addresses are important and that your project is likely to provide answers. They will then make an expert judgement and write a report and recommend a score that accompanies your application when it goes to the committee. They can probably spend several hours reading your application because, unlike the committee members, who get a big bundle of applications at once, referees get sent applications one at a time.

The Layers of a Case for Support

These three groups have very different needs. Any group can kill an application, so you have to write something that appeals to all the groups. It also helps if what you write gives them a common language to discuss the case for support. The magic formula constructs the application so that it consists of multiple layers that work together, to meet the needs of all the groups of readers without alienating any of them.

Top Layer: The Opening Sentence

The opening sentence has three tasks.

- It has to catch the interest of the ordinary committee member and make them feel that it might be worth reading a bit of your application even though they don’t know anything about the topic. I always begin the sentence with a ‘big picture’ statement about the goal of the project. It is important to express the statement in language that will be intelligible to ordinary committee members.

- It has to speak to the expert in a way that will reassure them that your project has some real ‘meat’ to it despite the rather bland and aspirational ‘big picture’ opening. I try to make sure that the sentence continues with a much more specific statement that builds trust in the methodological rigour of the project and the competence of the research team. Ordinary committee members probably won’t understand the detail here but if the opening statement is good enough they will accept that this is just a more specific version of it.

- The sentence must serve as a summary of the case for support, in case the reader chooses not to read on.

Second Layer: The Statement of your Case

The second layer of the case for support is a statement of your argument that you should be funded. The magic formula provides the argument in ten sentences, including the first sentence. These sentences are the first ten sentences of the case for support. I have already talked about the opening sentence. The remaining nine sentences are:-

- A sentence stating what makes the topic of the project important to the funder.

- Three sentences, each one stating an important research aim relevant to the topic, and a reason that research aim is important. The research aims might be couched in terms of hypotheses to be tested, relationships to be established, questions to be answered or in some other way. But in every case there will be something that could be achieved by an as-yet undefined research project, and a reason that it is important to achieve it. I call these sentences the problem sentences.

- A sentence giving an overall description of the project.

- Three sentences, each one describing the research in a part of the project, and what that research will achieve. The part of the project might be referred to as an objective, a work package, or in some other way. What the research will achieve will be expressed in the exactly same words as were used to express the research aim in the corresponding problem sentence. Using the same words makes it clear to every reader that all of the important research aims referred to in the problem sentences, will be achieved by the project, , whether or not they understand the terminology used to describe the research aims and outcomes.

- A final sentence saying what will happen as the project concludes.

This second layer provides all the readers with exactly what they need: a short simple statement of your argument that you should be funded. The essence of that argument is that your project deals with an important topic, and will achieve important research aims related to that topic. By expressing the research outcomes in exactly the same words you used to express the important research aims, the magic formula ensures that all the readers will understand that the project achieves those important aims, whether or not they understand the terminology used to express them.

This statement of your argument is probably as much as the ordinary committee members have time for, which is why you put it right at the beginning. You would now like to ensure that all the readers believe your argument and remember it. To do this you recycle the sentences from the introduction to create a framework for the detailed evidence.

Third Layer, Structure of Case for Support

The third layer of the case for support is provided by its structure. After the introduction there are nine more sections in the case for support. Each of those sections begins with one of the sentences from the introduction and contains all the evidence that you will draw on to convince the reader that the sentence is true. The section will also have a heading that is a shortened version of the first sentence.

Creating the framework from the same sentences as the introduction has the effect that, just by skimming the case for support, a reader will see that it marshals evidence to support every part of the argument in the introduction. If they already believe the argument, they probably feel no need to read on, which is probably the case if they are just an ordinary committee member. On the other hand, if they want to test all or part of the argument, they can see exactly where to find the evidence.

Fourth and Fifth Layers: Internal Structure of Sections and Paragraphs

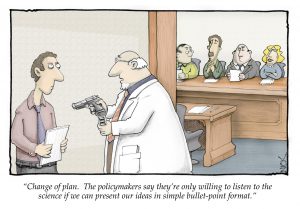

The referees and the presenting members want to know what evidence you are using to support each part of your argument. I recommend that you begin each section by stating the main points of the evidence. Then you make each point of evidence in a single paragraph. I also recommend that you begin each paragraph by stating the point you want to make. Then you use the rest of the paragraph to make the point.

The advantage of this hierarchical structure is that readers can find the detail they need if they want to test any of your points, which the referees probably will. However, readers who don’t want to test the detail, which the presenting members probably won’t, can learn what it is and then skip over it by looking just at the beginnings of the sections and the tops of the paragraphs.

The structure of the sections and paragraphs ensures that any reader can check the evidence you are using to support your case, at any level of detail. The fact that you make repeated use of the sentences you used to summarise your argument in the introduction helps readers to find their way through the evidence, and, incidentally, helps to make sure that they remember your argument and that they all express the argument in the same terms.

Sixth Layer: Summaries

Not all members of the committee will have time to read your case for support. To ensure that committee members who don’t read the case for support know its argument, I recycle the sentences of the introduction in any abstract, summary or statement of aims and objectives that forms part of the application form.